Becoming Stationary

Becoming Stationary

Not all of the people we covered in Lesson #1 went west through Europe. Others went south, where they found a place between two large rivers that was excellent for growing crops. That place is called Mesopotamia, which in old languages meant, “between the rivers.” The area is mostly inside of what we now call Iraq, and we call those rivers the Tigris and the Euphrates.

This south-going group soon learned that this wasn’t ordinary flatland, where crops got their water from the rains. Rather, this land flooded every year. So, after they learned how to grow their crops under this condition, they also found that they didn’t have to move along every few years: These fields were renewed by the annual floods, and produced a full harvest of grain every year.

During the flood season, which began in spring and lasted for months, melting snow from the northern mountains made the two big rivers overflow. During those months the farmers used irrigation canals to bring flood water to nearby fields that didn’t flood by themselves. (Animals were moved away to prevent them from drowning.) As the waters dried up, the farmers planted their seeds and then tended to their crops. Finally came the dry season when crops were harvested and stored.

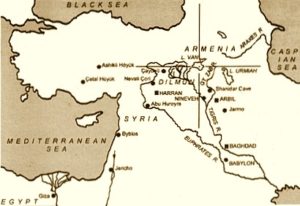

This cycle – and it was very reliable – allowed these people to remain stationary… to remain in place unless they wanted to move. (Similar things happened in the Nile, Indus and Huang Ho river valleys.) Here are some of their earliest settlements:

Remaining in one place allowed these farmers to store almost any amount of food, meaning that they could stop worrying about the future in a way they hadn’t before. It also allowed them to accumulate more tools (not just for farming, but for cooking and other things), more clothing, and more things of almost every kind. They no longer had to move, and so they didn’t have to worry about carrying it all.

All of this gave people free time in a comfortable place, which allowed them to experiment more, and to produce things like newer and better musical instruments. Large numbers of people began to do specialized work: cattle-raising, fishing, weaving, leather working, woodworking, and so on. We’ve also dug up things they left behind, including hoes, adzes (wood-working tools), pounders (stones used more or less like hammers), knives, sickles (for harvesting grain), brooms, loom weights (looms are tools for making fabric), and others.

One of the most important things they began doing at this time was producing large amounts of hard metals, either by melting them out of rocks or by a more complicated process called smelting. These metals were formed into strong, durable tools. Tin and lead had been smelted at Catalhoyuk (also where people could remain stationary), but those metals aren’t very hard; tools made from them don’t stay very sharp or last very long.

Copper, however, is much harder. It can sometimes be found in the ground, but not very much of it. There is, however, a lot of metallic ore (the ore for copper is called malachite, a greenish rock) that can be melted at high temperatures. That required thick clay ovens with a lot of air blowing into them, but it was soon enough accomplished. After that, the copper could be ladled out, poured into molds, and used as they wished. And so any number of durable tools could be made, not just a few.

This was certainly one of the more exciting times in human history. Important and highly useful things, things that were previously unknown, were arriving on every side. And the good times continued for centuries.

Violence Arrives

Stationary farming created large amounts of food (typically grain) which, if carefully stored, did not rot. Soon after, there were large amounts of other durable goods: clothing, furs, tools, and so on. By ancient standards, these farmers had become very rich. And while they were happy living cooperative, productive lives (we find no evidence of anything like war at Catalhoyuk or the other settlements of these people) there were others who operated, not by cooperation, but by plunder.

These farmers had become sedentary (settled in one place). And sedentary farmers are seldom skilled at violence. So, those who were skilled at violence, once they saw unprotected wealth, became a problem.

The first plunderers were hunters and/or herdsmen who became envious of the farmers’ wealth. They recognized that rich, stationary farmers were easy to rob.

These first plunderers seem to have believed in dominating gods, and told stories of the stronger dominating the weaker. One of the phrases that seems to come down to us from them is, “We should be the head and not the tail.” Repeating such slogans to themselves would make them ready to plunder the farmers. They were also experienced in capturing and killing large animals.

These plunderers were able to remove the wealth of the farmers, either to a safe place or simply to trade it. Almost certainly the first occasions of plunder were simple looting missions of this type. (Some of our earliest writings have stories of this.)

In some places, these looters were so successful that they drove the farmers away, leaving them to look for new victims or return to their previous lives. Before long, however, some of the looters developed a third option: Steal only a limited amount: not enough to drive the farmers away. This way they could work the same area every year.

And so began limited but persistent theft, performed by violent groups, under a leader of some type. (Some of our oldest stories indicate this, even naming the first big leader. The Hebrews called him Nimrod and the Greeks called him Ninus.)

For the farmers, it was easier to give a fifth of their crops to a thug than to run away or face violence. And so many of the farmers grimaced and paid what they had to.

This type of plundering seems to have begun by about 6,300 BC, in central and northern Mesopotamia. The Nimrods and Ninuses seem to have built public spaces (like a square or park) where the farmers brought grain every harvest and were given a token in recognition of their payment.

This type of plunder was expensive, and so it doesn’t seem to have spread quickly. Because the plunderers were ruling by force, they had to pay a lot of thugs. On top of that, the farmers were quite clear that the arrangement was immoral, and so they felt free to hide some of their grain, and perhaps even to kill one of the thugs when they could. (Which would make the remaining thugs demand larger payments.)

To deal with that problem, it seems that the leaders tried to create a very scary impression in people’s minds, so they’d be terrified to disobey them. Even so, this method didn’t spread very far or very fast. Eventually it was replaced with a much more efficient one.

**

Paul Rosenberg

freemansperspective.com