Efficient Plunder

Efficient Plunder

A new model of plunder began in southern Mesopotamia at about 5,400 BC. The place it began was a small city called Eridu (e-REE-doo), which later kings claimed was the place where “kingship descended from heaven.”

The great change of Eridu’s “kingship” was this: Rather than using fear and force, kingship convinced the farmers that they should hand over their grain because it was their duty to the gods. (It’s hard to tell exactly what god or gods these people previously believed in, but they clearly believed in some.)

To make that process work, a new version of Inanna’s story was created, saying that she had to travel to Eridu in order to receive the gift of civilization. Temples were also built, with altars (tables), upon which people were expected to offer grain to their god.

People left things of the altar with some type of ceremony, and the caretakers (priests, more or less) removed the offerings, quietly and probably without being seen. These altars weren’t remotely big enough for offerings of grain at harvest time (for that, public squares were still used), but repeated offerings upon them got people used to sacrificing to the gods, and trained them to see it as a holy obligation… to see handing over their crops as a noble thing.

Here is an archaeological drawing of the earliest temple and altar, at Eridu.

It was at this point that a Mesopotamian religion came together. It certainly involved the necessity of sacrifice, also a person’s duty to their ancestors. And so, small sacrifices to the gods for the sake of one’s ancestors were made common, and large sacrifices at harvest time were enforced. These became sacred duties.

It was at this point that a Mesopotamian religion came together. It certainly involved the necessity of sacrifice, also a person’s duty to their ancestors. And so, small sacrifices to the gods for the sake of one’s ancestors were made common, and large sacrifices at harvest time were enforced. These became sacred duties.

Once this idea stuck, kingship (rulership) became much easier, and the model spread quickly, all through Mesopotamia and then into Egypt.

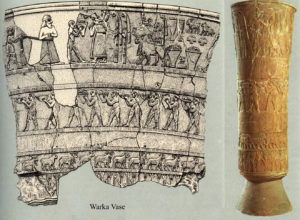

You can see this model very clearly in a vase recovered in Mesopotamia, from the era of perhaps 3,500 BC (possibly earlier). It’s called the Warka vase, and shows farmers bringing pots of grain and animals from their herds to a temple, then handing them to the representatives of the god. Put simply: the farmers brought their sacrifices and were told they were good people for doing so. The priests collected the sacrifices and shared them with the kings. People who didn’t sacrifice were punished, not as disobedient people, but as dangerous people.

Here’s the Warka vase:

It’s important to understand that this Mesopotamian religion was a collective religion rather than a personal religion. In a collective religion, one person angering the god would cause the god to injure (or withdraw protection from) the whole city. In a personal religion, a man or woman displeasing the god might suffer personally, but the god wouldn’t punish everyone for one person’s crime.

It’s important to understand that this Mesopotamian religion was a collective religion rather than a personal religion. In a collective religion, one person angering the god would cause the god to injure (or withdraw protection from) the whole city. In a personal religion, a man or woman displeasing the god might suffer personally, but the god wouldn’t punish everyone for one person’s crime.

It’s also important to understand that each city had a specific god, and the god was treated as the owner of that city or town.

As time went on, the cities of Mesopotamia increased in size and number, and added other pillars of “kingship.” One was that order (enforced by rules) was absolutely necessary. Others were accounting, a collective identity (that they were attached to their city), a rulership-alligned intellectual class, impressive buildings, and an endless fight for status: to be above or better than everyone else.

By this point, we see a large group of people living in a complex but consistent way. And the name we apply to them is Sumerians. (They called their land Sumer.) Using this name can get complicated, since there were many different rulers over time, and specialists like to use separate names for each ruling group. But the way people lived changed very little, no matter who the rulers were.

As you read about groups of people, there are a few things you should be aware of:

-

- Since there have been so many millions of people, we often have to look at them as groups: our minds are simply not able to hold the life stories of thousands of people at the same time.

-

- When thinking about people as groups, we should remember than all humans are individuals, When we talk about groups, we’re trying to describe a large number of people with just a few words. Such descriptions will always be partial.

-

- People use names for groups of people, generally defining them as “cultures,” “societies,” or “civilizations.” And they sometimes treat these words as if they have special importance, which they don’t. All of these words mean, “a group of people who share a set of ideas.” A large group of this type would be called a “civilization,” and a smaller one a “society” or a “culture.”

-

- It is individuals who create every society or civilization, mainly by teaching their children the ideas they think are most important. Societies and cultures aren’t real things; they are descriptions of real things.

As this Sumerian model of life and rulership expanded, local kings cooperated with regional kings, or simply had their kingdom swallowed-up by them. This led to “kings of kings,” also called “emperors.”

At one point, there were so many cities of this type in Mesopotamia that they were almost within sight of each other.

**

Paul Rosenberg

freemansperspective.com