Issue #24 / June 2012

Download PDF

The one section I had to pass over in last month’s coverage of Locke’s Natural state was organized aggression. I did that because organized aggression is a more complicated subject than the others we examined.

The principles of resisting aggression are the same, whether for individual crimes or larger, organized crime, but the implementation of organized aggression has been both complex and effective. It requires a more thorough examination.

But I want to do more that just examine the principles of organized aggression – I want to show precisely how it overtook men in their natural state. This requires a look far back into human history, but it can be done, and I think it is a very important and illuminating thing to do.

Bear in mind that the material we cover here will be new to you. You were not taught this in school and it does not show up on television shows, even the history shows. You will be able to verify most of this on Wikipedia, but not in traditional sources. You can find artifacts telling this story in museums as well: in particular in the Pergamon museum of Berlin and the British museum in London. (But be careful to follow the artifacts, not the explanations written in the signs.)

What I write here are broad generalizations, of course – one cannot write of 8000 BC in precise particulars – but I am confident that it is a close representation of what happened.

BACKGROUND

Before explaining how organized aggression took shape, it is important to clarify the first situation. Our “dawn of history” was this planet’s most recent re-start. Earth’s most recent ice age ended between 9000 and 8000 BC, after slowing down (erratically) for several thousand years prior.

At this moment, the people we will be following found themselves – almost purely – in a condition matching Locke’s natural state. There were only about five million people on the planet at that time, and most of them were in equatorial regions (where they remained), in the far East, or in the Western hemisphere. So, some thousands of people left their ice age hideouts and ventured into many million acres of newly available land.

The group of early people I am most interested in are the first real farmers, who were also the original source of what became Western civilization. (As well as Greco-Roman civilization, the Minoans, and the Sumerians before them.) These are the people who populated Europe and who became the first innovators in a hundred different fields.

We actually know little about the other groups that survived through the ice age:

We know something about those in central Europe from the drawings they left behind. We know that people in the Middle East survived by gathering figs and dates. Many humans survived the ice age in Africa, the Americas and the Far East, but relatively little is known of them.

THE FIRST WAY OF LIFE

When seeking to understand how our ancestors lived, it is important to reset our imaginations; in particular to stop thinking of ancient men as dim-witted and unimaginative. This is false. There has been no significant change to the human species in 30,000 years, and perhaps not in 100,000 years or more. Images of grunting cavemen are self-flattering nonsense. We are them; they were us.

Now, to continue: The farmers mentioned above came down from Armenia at the end of the ice age. Some time previously, they had discovered something of great importance: The willful production of wealth via intelligent use of the natural world; in other words, farming.

These farmers slowly made their way from Armenia to the west as far as England (where Stonehenge remains as a monument to them) and to some unknown distance to the East. Having not yet discovered crop rotation, they tended to move from one field to the next when the first field’s production waned. This was no problem, since the world was all but empty at that time.

It seems that these farming groups kept a tradition to gather in much larger groups for a few weeks every year. A standing monolith and building, dated to approximately 8,000 B.C. at Nevali Cori in western Armenia, was probably one of these ancient meeting places. It was located only three kilometers from the southern bank of the Euphrates River, a convenient meeting place. Gobekli Tepe, with its open-air observatory, was all but certainly another meeting place.

These gatherings would have been very much like the camp meetings of Methodists and other religious groups in the 18th and 19th centuries. Like them, they would have included exchanges of information, joint planning and marriage arrangements.

THE FIRST “RELIGION”

I put the word religion in quotes here because it is uncertain that the people who appeared in Armenia after the ice age had what we would call a religion. Modern people merely presume that ancient humans were highly superstitious, but presumptions are not evidence. This automatic conclusion was born in the Enlightenment period, when the idea was instilled that ancient = primitive = superstitious.

For certain instances, this Enlightenment supposition may be true. But to assume that it is 100% true, and then to extrapolate it backward over nine millennia is bad reasoning and of no value as evidence.

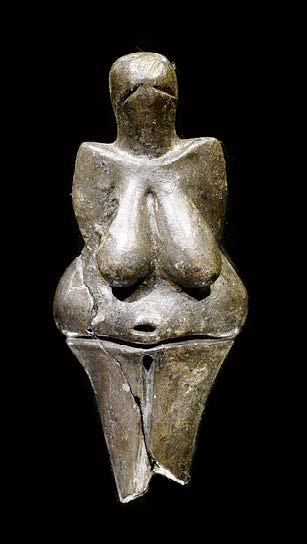

From the ice age, only one type of artifact that can be called religious has been found, though found in many scattered places, and those are called Venus statues. They were widely distributed at least as far back as 35,000 BC. The one displayed below is from Moravia (in the modern Czech Republic) at about 27,000 BC.

The descriptions Venus statue, or Goddess, however, are merely modern descriptions. We have no idea of what people thought of these figures in 35,000 BC. We have an idea of how they thought of them in about 8,000 BC, but that is a long, long time afterward. The conceptions at both times may have been similar, but it would be extremely foolish to simply pass off 27,000 years as a period in which nothing changed.

The largest known settlement from the period just after the ice age was discovered in 1958, at Catalhoyuk, Turkey. It dates to about 7500 BC, as the first farmers were slowly spreading across the Western hemisphere.

At Catalhoyuk, many well-formed, female figurines were found, carved or molded from marble, limestone, schist, calcite, basalt, alabaster, or clay. It is presumed – and probably correctly – that these figures represented a goddess, whose name first appears as Inanna. This name was derived from a language that preceded Sumerian and was probably the language of the first Western farmers((This language analysis comes from Samuel Noah Kramer, in a book he co-wrote with Diane Wolkenstein, called Inanna.)) – the ones who appeared at the end of the ice age, coming south and west from Armenia.

It would be a mistake to assume that the ancient goddess was like a dominating male god, but of the other sex. Male gods developed among the nomads and foragers of the south, and were generally conceived of as dominating storm gods, who would strike from above. There is absolutely no reason to think that the female god was thought of in the same way. In fact, there is a good deal of reason to think otherwise.

A female god indicates a cooperative culture… like a farming culture. This is not because there is some superior value in being female, but because of the creation and productivity that a woman embodies: Her body literally brings forth new human beings.

This early female god was not a dominator, she was a catalyst – not striking from above, but working with. She was a magic embodiment of the creative and productive principle.

PROSPERITY, ENVY & WAR

The great discovery of these farmers was that by using the world creatively, they could produce much more food than they could have previously. And then – how and when I cannot tell with any precision – they began to apply that principle in many other ways. These people learned that they could mold nature to their uses, and to prosper far more, and in far more ways, than any other people ever had.

These early farmers, for the first time we know of, discovered a strongly post-parasitic way of living on earth. They did not feed off of what already existed. Instead, they became active and made the earth produce food for them.

This, of course, created an unpleasant contrast between the farmers and the hunters that they encountered on their slow movements to the south and west. Consider this:

- Young nomads were instructed by their way of life to take, from a world of limited resources.

- Young farmers were instructed by their way of life to use the world intelligently and to create food.

Farmers not only produced more than the nomads, but they had discovered how to use their minds and to produce more and more.

The nomads lived by a plunder model and tended to look at themselves as the dominators in the midst of a world of limited resources. So, when these people met the rich farmers, they naturally tended to compare themselves to them, and to become angry at what they saw.

Very quickly, the hunters formulated reasons to hate the farmers. The real reason, of course, was jealousy.

It seems to be a nearly universal phenomenon that effective farmers stir violence on the part of nomads and foragers. Below is a drawing copied from a prehistoric rock painting in South Africa. It shows foragers on the left, firing arrows at farmers on the right.

This superiority of the farmer was increased in the plains of Mesopotamia where they were able to become stationary. Food was plentiful, goods could be accumulated, and large communities could be formed. This led to immense variety and specialization. Music appeared in variety and with many experimental new instruments. Written language may have developed, along with basic mathematics and more. It was the birth of man’s intellectual life.

For all the reasons mentioned above, conflicts between these groups were almost certainly common, and likely universal.

RAIDS AND DEFENSE

By any ancient standard, these farmers were stunningly rich. And while our farmers were happy living cooperative, productive lives, the jealous nomads were unhappy with the situation. They responded by attacking and plundering them.

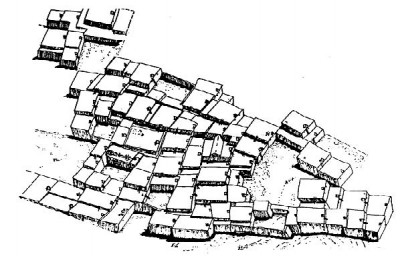

These people organized their lives around the need to protect themselves against raiders. We don’t know much about the weapons they employed, but we do know that they made it very difficult for raiders to attack them.The image below is the settlement at Catalhoyuk. Notice that the entry to each house is on the roof. Ladders were required to enter or exit. This was done for one reason: security.

In addition to the absence of doors for entry, the roofs of these houses joined each other, turning them into broad walkways – almost a rooftop park. That makes it very easy to mass defensive force at any specific point. It’s actually a brilliant defensive adaptation, and it apparently succeeded quite well. We have no record of the successful plunder of this type of settlement. While it is true that we have limited evidence of any type for this period, we have found successful settlements but not conquered settlements.

You can see the interior of one of these homes (reconstructed) in the image below. Note the ladder to the roof.

THE FIRST SUCCESSFUL AGGRESSIONS

Aggression has an inherent weakness: Every act of aggression is a net destroyer of property and production. Too much aggression and there is nothing left to steal. The producers either die or run away.

For aggression to be effective over time, the producers – the necessary target of all predators – must be immobilized, and, if possible, be made to cooperate with the predator.

Raiding parties can very effectively steal from stationary producers, but only within limits. Consider:

- If the producers are killed, their production – next month’s plunder – is lost.

- If the producers are chased away, all future plunder is lost.

- If the producers organize themselves and fight back, additional violent associates must be found, which means less plunder for the existing associates. In addition, as associates are injured or killed by the producers, the remaining aggressors will demand increased compensation.

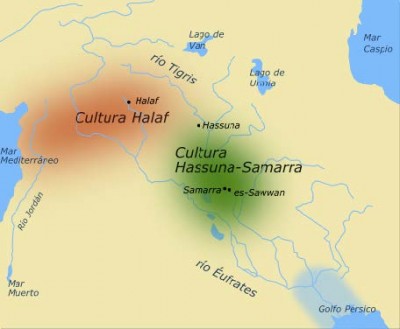

The first successful aggression occurred in the areas of central Mesopotamia illustrated above, at some time prior to 6100 BC.

The slowly migrating farmers mentioned above made themselves stationary in central Mesopotamia at some point in the 7th millennium BC (6001-7000 BC). The Tigris and Euphrates rivers flooded the surrounding area every year, restoring the fertility of the fields, and making migration unnecessary. And by digging some irrigation ditches, this naturally renewed area could be spread very significantly.

This is where the farmers became stationary. Almost certainly they had passed beyond the range of the northerly raiders that threatened Catalhoyuk and were temporarily safe. Even so, it seems that they kept their earlier custom of staying a few miles away from the big rivers. Nineveh, for example, existed on a side river, about three miles from the Tigris. (This was at 6000 BC, or perhaps earlier.)

And being stationary, they could store valuable goods, as well as devoting more time to invention. This is where woodwork, leatherwork, music, art and a hundred other things first flowered.

The rulers of the 6000s BC left no specific structures of rulership except the city square – a place for public assemblies. These would also be the locations where taxes were paid, mainly at harvest times.

The other clues we have about organized aggression at this early date are the legends of first rulership; in particularly the legend of Nimrod. The Hebrew record has Nimrod as “the first on earth to be a mighty man,” and further that he was the first man with his own legend, that of “the mighty hunter.”

These legends may or may not be true, but legends do (and often quite accurately) tell of ancient developments and/or events.

Furthermore, the cities of Nimrod were precisely those of central Mesopotamia, as the Hebrew Bible records:

The beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar.

An ancient Greek historian named Diodorus Siculus also has Nimrod (using his alternate name, Ninus) as the first to rule over groups of men:

Ninus, the most ancient of the Assyrian kings mentioned in history, performed great actions. Being naturally of a warlike disposition, and ambitious of glory that results from valor, he armed a considerable number of young men that were brave and vigorous like himself, trained them up a long time in laborious exercises and hardships, and by that means accustomed them to bear the fatigues of war, and to face dangers with intrepidity.

We can draw no proofs from these legends, but they do lead us to believe that the first rulers of Mesopotamia were an organized, disciplined group of thugs, led by a classic “big man.”

The fact that Nimrod (or Ninus) had a legend supports the belief that he ruled a number of cities. The purpose of a legend is to maintain an influence over a distance. It would be superfluous for people with whom you lived every day: they see you directly and need no legend.

It is thus likely that the first rulers in central Mesopotamia set up public squares, installed associates to watch over the farmers and to observe the harvests closely so that the big man got his full share. Interestingly, the Hebrew word for “city” in the ancient texts also has the meaning “watched place.”

Eli Wallach, in the film The Magnificent Seven, plays a very vulgar type of Nimrod figure, and his followers a vulgar type of the first violent organizations. In all likelihood the first big man was more intelligent and disciplined than the Wallach character (and not on horseback), but that portrayal is the closest I know to first rulership.

This style of rulership existed in central Mesopotamia from perhaps 6300 BC to 5300 BC, but it seems not to have spread much further. It is likely that small groups of farmers escaped and started free communities further south… and that the ruling thugs lacked manpower to extend their rule that far.

To date, the only record of this Nimrodic rule is in the areas mentioned above. That would make sense, since simple thuggery is expensive. Forcing people to hand over their produce requires lots of manpower, and all those thugs require compensation. Furthermore, thug parents don’t always produce thug children. The history of the Vikings, for example, shows that the second generation is very often happy to take up farming rather than conquest. That requires new thugs to be recruited and trained. Again, that is limiting.

On the farmer’s side, giving a fifth of his crops to the thug every harvest was a lot better than facing death, or going back to being a traveling gardener or a forager. So, he grimaced and accepted it, as do most modern men.

KINGSHIP DESCENDS

There is a big difference between Nimrodic thuggery and what the Sumerians called kingship (and which I refer to as rulership).

The kingship developed at Eridu was a quantum leap from that of first rule. Rather than majoring on intimidation, kingship convinced the producers that they should turn away from their own judgment and desires, and that they should give the king what he wanted, willingly.

Here are historian Will Durant’s observations on this process:

The state, in order to maintain itself, used and forged many instruments of indoctrination… to bind in the soul of the citizen a habit of patriotic loyalty and pride. This saved thousands of policemen, and prepared the public mind for the docile coherence which is indispensable in war.

While Nimrodic rule manipulated men’s actions, kingship manipulated men’s wills. Doing this was probably the greatest “evil genius” moment in human history. In short order men were trained to not only hand over their goods, but to see doing so as their service to the gods, and to teach this to their children as a virtue.

This new way of life set plunderers as a respected class of beings. Never before had producers respected their plunderers as a group: They feared them, they grudgingly cooperated with them, but they did not respect them. After Eridu, they did.

The new rulers of 5400 BC seem to be a new group, and they seem to have come from the Caucuses; the southern part of the area that would later be called Rus, and still later Russia. The first reason to think so is that they worshipped sky gods rather than the storm gods of the Nimrodic rulers. These new gods lived on a high mountain, like the Greek gods were thought to live on Mount Olympus. Another intriguing clue is that these new rulers always called themselves “rulers of the black heads,” as if their hair were lighter than their subjects’ hair.

Since Eridu was at the south of Mesopotamia, it is uncertain how these new rulers arrived. It would seem that they came down from the north on the rivers, bypassing and surveying the existing city-states, until they reached the Persian Gulf.

But, regardless of their origin, these people instituted a new ruling scheme with a clear focus on mythology as a primary tool. This is the same basic model that was used in Egypt, but these people preceded Egypt by two thousand years.

These new rulers displaced the nomadic thug rulers and probably left them as middle managers as they worked at spreading their new model of kingship and stringing city-states together into an empire.

THE INVENTION OF SACRIFICE

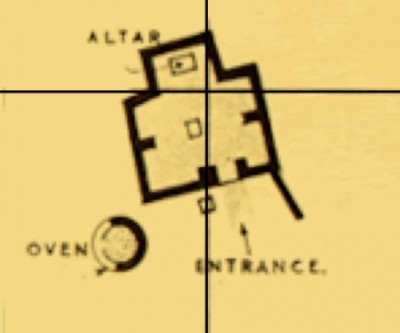

This small temple and altar is quite likely where the practice of sacrificing to deities began.

Before this altar was built in Eridu, at about 5400 BC, people probably did not sacrifice to the gods. I know that this is contrary to accepted wisdom, but it appears to be true. And, for what it’s worth, it was a conclusion that troubled me when I came upon it.

The image above is a section of the excavation plan from Eridu, at a bottom layer, and it was here, so far as can be seen, where the practice of sacrifice originated.

Since this is, so far as I know, a new understanding of the ancient past, I would like to state the facts that I base this upon:

- No report of a sacrifice to a god earlier than this date has ever been found.

- There have been no artifacts found, prior to this date, indicating sacrifice to a god. A few archaeologists have said things like “this may have been associated with offerings,” but those are merely guesses based upon naked assumption. One of these appeared in the June 2011 National Geographic story about the Gobekli Tepe excavations. It was a habitual grasp at a maybe.

- An altar with a table in front of it very clearly appears in Eridu at about 5400BC, and Eridu was very clearly the origin point for the rulership model of Mesopotamia. The Sumerian list of kings begins with these words: After kingship descended from heaven, Eridu became the seat of kingship.

- Immediately after the founding of Eridu, with its sacrificial altar, every other new city in Mesopotamia featured the same thing. Excavations at Tepe Gawri, for example, revealed a temple decorated with pilasters and recesses at 5000 BC. Samuel Noah Kramer, arguably the greatest of Assyriologists, says that two features characterized all of Sumer’s Temples: A niche for the god’s emblem or statue, and a mud brick table in front of it for offerings.

- Earlier Mesopotamian cities have been excavated and none have displayed temples with altars.

- None of the very early archaeological sites (7000-9000 BC) had temples and offering places.

It is possible that other peoples arrived at the practice of sacrifice independently, but there is currently no evidence to think so, and it is more likely that they picked up the practice from the Eridu model, after 5400 BC.

What this means is that offerings to gods were initiated under the new pattern of rulership in Eridu. It further seems that sacrifices were instituted for a single reason: to train the populace in the willing surrender of their goods, and to associate such acts with righteousness.

This invention was, as Durant says, an “instrument of indoctrination, to bind the soul of the citizen,” and it continued for a long, long time. Moreover, the concept of sacrifice continues in many religions and through much of the world today. The truth of its origin, however, is far from laudable: Sacrifice was invented and institutionalized to train humans in rejecting their own will and handing their goods to other people, willingly and even gratefully.

This may seem cruel. After all, many good people have described their best and bravest moments with the allegory of sacrifice; this discussion might seem to classify them as fools. But that is not so and they were not fools. They may have described their good deeds badly; they may have thought of them incorrectly; but saving life is a good thing. It is good, however, not because sacrifice is good, but because life is good; it is noble to value it and heroic to preserve it.

This concept will be a difficult one for some religious people, who have thought of sacrifice as service to God, as well as to statists who consider taxation to be their righteous duty. Nonetheless, the facts now stand in the open. I’m sorry if it hurts.

With sacrifice in place, priests were added and the northern sky gods seem to have been placed above the previous production goddess Inanna (who they dared not remove entirely), and new myths were propagated accordingly. In one, for example, a god named Enki replaced Inanna as the source of fertility.

This willful, top-down changing of the gods is not unique of course; a very similar process took place as the Catholic Church absorbed the previous gods and traditions of Europe and rolled them in to Catholicism.

OTHER INTERPRETATIONS

As I say, I seem to be the first to notice that sacrifice begins at Eridu. That being the case, I looked for alternative theories and found nothing in print about it. It is a subject that is not discussed, so far as I was able to tell. In discussions, I found one alternate theory, which is that sacrifice always existed, but that it was institutionalized first at Eridu.

This era of the natural state – what could be called the Inanna time – can be looked at based upon the artifacts that these people left us, or it can be examined by looking backward from Sumerian history.

There are two problems with looking backward from Sumer:

- Sumer is a much, much later era. Sumer began 5000 years after our first farmers came down from Armenia. That would be like us interpreting the Pharaohs of Egypt based upon Nasser, Sadat, the Muslim Brotherhood and the Arab Spring. Even the time between Eridu and Sumer was 3000 years. .

- Sumer had hundreds of gods, some of which may or may not trace their history back to the time of the first farmers. Each city had its own gods and its own legends; these stories point in many directions.

For these reasons, I am willing to look backward from Sumer to find continuing threads and to follow the development of ideas, but I am unwilling to pick a story and base nearly everything upon it.

THE PILLARS OF KINGSHIP

The Eridu model of rulership that was completed by the Sumerians had or developed a number of primary characteristics:

Order. Organization was a crucial and central issue to the Sumerian rulership that began at Eridu. One of the major myths maintains that “without Enlil (the sky god), workers would have neither controller or supervisor… no cities would be built, no settlements founded.” So, not only was organization paramount, but it was thought of as originating with the gods. (And therefore being unquestionable.)

Kramer described another Sumerian myth as meticulously dividing civilization “into over one hundred culture traits and complexes relating to man’s political, religious and social institutions, to the arts and crafts, to music and musical instruments, and to a varied assortment of intellectual, emotional, and social patterns of behavior.”

Accounting. Above all things recovered from ancient Mesopotamia, by far the most common are accounting and property records. Thousands upon thousands have been found. Ninety percent of all recovered texts are administrative and economic records. Public buildings and temples were halls of records, where apparently every significant business transaction was recorded.

This is where accounting was originated, and it had a single purpose: to establish a pattern of reporting to a government that collected taxes on all that was recorded. That’s not to say that accounting has no other useful applications, but this is clearly how and why accounting began.

A state-aligned intellectual class. The scribes of Sumer were closely aligned with the state, while not being actual rulers themselves. (Priests were aligned too, but it may be better in this case to call them rulers.) There were many scribes – recording innumerable business transactions – and they were highly specialized in types of administration. Over time they became leading officials. Sons of officials became scribes.

To illustrate how closely scribes were associated with the rulers, one teacher is recorded making this benediction to his students: May you satisfy all those you walk to and from in the palaces.

Another conversation is recorded, of two young scribes arguing which one knows how to do his job better. It shows that they were doing the work of defining ownership and assigning value. One of the belligerent scribes says, When I go to divide an estate, I divide it… when I go to survey the field, I know how to hold the rod.

Surveillance. From Eridu onward, groups of cities were built around temples, eventually almost within sight of one another. It is important to remember that the cities we are discussing here were small by modern standards. That meant that the ruler – and certainly a scribe – was never terribly far away and there was often no dark corner to hide in. The watcher was close and records were kept. Hiding was difficult.

This is important because surveillance kills the heartiness of thought and the possibilities of unapproved paths. Regulation forbids adaptation.

Fear. The rulers of Eridu didn’t use guilt, as has become popular since that time, but they did use fear and intimidation. Samuel Kramer writes this:

From birth to death, the Sumerian had cause at times to fear his parent, his teachers, his friends and fellow citizens, his superiors and rulers, he foreign enemy, the violence of nature, wild animals, vicious monsters and demons, sickness, death, and oblivion.

We know, for example, that in the city of Lagash, people were imprisoned because of debts, grain due to the palace, and barley due to the palace stores. An old inscription complains: From the borders of Ningirsu to the sea, there was the tax collector.

Another old inscription mentions “the supervisors of the plain and the watchers of the fields.” Another, from one ruler to another, says, “make the people obedient; make firm the foundation of the land. It is urgent.”

Government buildings and monuments. Another innovation from Eridu was the monumental temple. Temple complexes separated ordinary men from their rulers. Restricted passages, courtyards, and great stairways had to be traversed in order to reach the important places. This instilled the idea that the rulers and priests were of a different class than average men. They were literally above and figuratively above.

When a common man was given access to the special places, he felt as though an honor was bestowed upon him. He had attained a special status and enjoyed the feeling. He would now be considerably less likely to turn against the regime.

Competition, ambition and prestige. Being controlled reduces men’s natural vigor and production. At some point (and exactly when is uncertain), production was boosted by stoking competition.

Limited and desirable rewards induced the most aggressive males to work excessively to obtain them. A lust for “success” was used to drive men in the face of meaninglessness; the cultivation of status impelled them even as the bulk of their rewards were taken away. Position became a replacement for production. Kramer described this as an ambitious, competitive, aggressive, and seemingly far from ethical drive for pre-eminence and prestige, for victory and success.

As in our day, there was great competition in systems of formal education. “May you rank the highest among the school graduates” is found among Sumerian inscriptions, just as it can be found among ours. Again, Kramer describes the situation and its results:

The drive for superiority and prestige deeply colored the Sumerian outlook on life and played an important role in their education, politics and economics… which sparked and sustained the material and cultural advances for which the Sumerians are not unjustly noted.

This aggressiveness, however, could not be contained within city-states. It spilled over into fights between the states, which were “bitter and consistent.”

Reassurance mechanisms. Kramer in one place comments on “the emphasis on law and legality, the penchant for compiling law codes and writing legal documents, which has long been recognized to have been a predominant feature of Sumerian economic and social life.”

Law was used to comfort the populace with the idea that they had rights and that they could always appeal to the law. (That was sometimes true in our late middle ages, but not for these people.)

Rules, once set, relieve the rule-maker of the difficult job of convincing each person to obey. “It’s the law” is the only ‘reason’ required. Rules, by their nature, exclude reasoning. Further, when it is a rule that removes goods from the producer to the rule-maker, it is impersonal and less offensive. Aggression is masked by the rule.

This is historian Will Durant’s explanation of the same concept:

Above all, the ruling minority sought more and more to transform its forcible mastery into a body of law which, while consolidating that mastery, would afford a welcome security and order to the people, and would recognize the rights of the “subject” sufficiently to win his acceptance of the law and his adherence to the state.

A later Sumerian reassurance mechanism was republican or democratic representation. The Gilgamesh epic refers to upper and lower assemblies – the same basic arrangement we have today – at about 2500 BC.

Collective identity. Just about every national group today has some sort of nation self-image, myth or identity. This idea has roots in Mesopotamia. Here are some of Kramer’s comments on the subject:

The Sumerians thought of themselves as a rather special and hallowed community more intimately related to the gods than mankind in general – a community noteworthy not only for its material wealth and possessions, not only for powerful kings, but for its honored spiritual leaders.

Patriotism, love of country, and particularly love of home city, was a strongly motivating force in Sumerian thought and action.

Sumer, in nearly all the old inscriptions, was simply referred to as “the Land.” The inhabitants of a city were known as its “sons” and were considered a closely related, integrated unit.

Public displays of uniforms, offices, flags, pageantry, myths, and common enemies not only create a collective identity, but they also soothe the minds of the petty enforcers who are essential to any ruling structure.

THE INTERNAL CHANGES

By 2000 BC, the long series of kingship adaptations had wrought many changes on the people of Mesopotamia.

At 8000 BC they had been in Locke’s natural state. They had lived, created and loved as they wished. They spread out over what is now Europe and were the first cultivators of the continent. They spread to the east some unknown distance. Where they were mobile, they repulsed – so far as we know – all the raiders who threatened them.

When they became immobile and accumulated goods, however, the raiders gained an advantage. A group or groups of intelligent raiders were able to establish a thuggish system of rulership in central Mesopotamia. This rulership was limited, and people of the natural state escaped to the south and seem to have been left alone for some centuries.

Then, a new system of kingship took hold in the south and quickly spread to through the entire Tigris-Euphrates valley. This new system minimized control of men’s bodies and maximized control of their minds, and especially their wills. This proved much more effective, and has been followed to a greater or lesser extent ever since – from one end of the habitable Earth to the other.

Organized and cultivated control of the human mind and will changed people. They became intimidated, ashamed, afraid to use their own judgment, desperately reliant on permission to act, and deeply mistrusting of their own natures. They had changed, and fallen far from their original confident state as the only intelligent, creative beings known to exist.

Samuel Noah Kramer describes the final products of this process – the people we now call Sumerians – in this way:

A Sumerian tended to take a tragic view of his fate and destiny. They were convinced that man was fashioned from clay and created for one purpose only: to serve the gods by supplying them with food, drink and shelter so that they might have leisure for their divine activities.

To further illustrate this at about 2200 B.C., a Sumerian father writes this to his son:

Do not speak ill, speak only good. Do not say evil things, speak well of people. He who speaks ill and says evil—people will waylay him because of his debt to [the city god]. Do not talk too freely, watch what you say. Do not express your innermost thoughts even when you are alone. What you say in haste you may regret later. Exert yourself to restrain your speech.

Worship your god every day. Sacrifice and pious utterance are the proper accompaniment of incense. Have a freewill offering for your god, for this is proper toward a god. Prayer, supplication, and prostration offer him daily, then your prayer will be granted, and you will be in harmony with god.

Note the caution, the uncertainty of mind, the fear of being impious. This is what control, regulation and fear breed. It created a mass of people who were easy to rule but unable to adapt, arise or create. Thus Sumer was overrun by newer, somewhat more Nimrodic rulers: The Babylonian, Hittite, Assyrian, Kassite and Elamite empires.

THE LOST NATURAL STATE

Since the invention and spread of kingship, there have been very few instances of men living in their natural state. Natural liberty was overcome by the innovations of Eridu and was lost to us.

Allow me to conclude with this:

The farmers from Armenia, who first discovered production and who lived in freedom, had a type of icon for that way of life: Inanna: the goddess of production and motherhood.

As it happens, the Sumerian word for freedom has mystified all the scholars. Its literal meaning is return to the mother.

It may be that whoever coined that term understood something that is now becoming clear to us:

That freedom is found in a return to the way of life – and, more precisely, to a state of mind – that was originally characterized by Inanna, the mother of production… and that the Inanna state is the same as John Locke’s “natural state.”

* * * * *

Once again I that this is enough for one issue.

See you next month.

PR