The Second Europe

The Second Europe

Europe, by 1300 AD, had a very specific flavor. Things differed from place to place, of course, but the life on the continent was now fairly uniform, and far better for most people than it had been under Rome. (Elites didn’t have it as well.) But as groups of humans do, these people began to solidify their arrangements: to see rules and hierarchies as more fundamental than real things.

Technology drove a good deal of positive change during this time. Paper was being produced in Spain by 1100, windmills (for pumping water and grinding grain) and magnetic compasses were being used in England by 1185. Boats were being built with rudders by 1180 and modern numbers replaced Roman numbers by about 1200. Eyeglasses had appeared in Europe by about 1250.

Agricultural technology was also crucial. European farmers had by this time switched over from the Roman model of crop rotation (two-field rotation) to the much more productive three-field model. They had also invented much better plows. Because of these things, far more food was being grown that it had been previously. This was a tremendous benefit to these people in both health and comfort.

By 1200, the Roman Catholic church was dominating Europe. Most of the competing Christianities had been pushed out in one way or another and the Church had become a strong hierarchy, separate from Eastern Christianity. It had, more or less, a monopoly on Christianity in Europe. It also had the allegiance of kings, who sought legitimacy from them and were often afraid of them. More than once, a king had to publicly humble himself before high church officials, formally apologize for something, and then be granted forgiveness. For a ruler to be excommunicated (cast out of the Church officially) could be disastrous and even deadly.

As we noted in our early lessons, rulers who are seen as legitimate have a much easier time gathering taxes from their subjects. Without legitimacy, rulership becomes difficult at best.

But before going further, it’s important to add that while the Church (especially at the top of the hierarchy) was involved in quite a few questionable and even openly immoral things, there were always local priests, monks, nuns and lay members who spent their lives helping the people of their parish; who, rather than abusing people; worked to feed the hungry, to support the widow and orphan, to guide the errant child and to strengthen the struggling adult. These things mattered a great deal. Europeans expected to see Christian goodness in the world and they did see it.

Because of the abundance of food and especially because of new commercial opportunities, more and more people began coming to the cities of Europe.

As another consequence of more food and money, local monarchs, the rulers of medium-sized areas, had an easier time collecting taxes, which were now often being paid in money rather than farm produce. When people are doing well, it’s easier for them to pay a bit more to the local ruler than to fight about it. And so the takings of rulers increased at this time.

But with a money-based economy, the monarchs (kings and princes) needed people who were literate and numerate: people who could read, write and calculate accurately. Rulers at this time mainly busied themselves with fighting, not learning.

And so, the cities began to be centers for a new intellectual class, and with them many more merchants and traders.

It was also at this time that major trading groups formed: The merchants of Venice, Genoa and Pisa in the Mediterranean, the Hanseatic League in the North Sea, and still others.

Legitimacy Wars

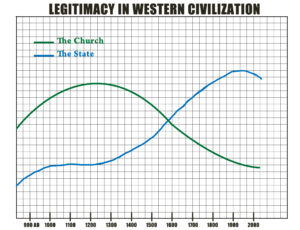

At this point Europeans monarchs saw a chance to take legitimacy away from the Church and keep it for themselves. This graph shows approximately how this changed over time, as the Church’s legitimacy peaked shortly after 1200 AD, then declined as the legitimacy of the rulers rose:

It was during this time the people began identifying with their “nation,” rather than as being part of Christendom or residents of a smaller area. In other words, they began to see themselves as part of a large and strong entity. This is really the same as saying that “legitimacy was shifting from the Church to the king.”

This continued over the next few centuries with larger wars than Europe had seen for many centuries (it takes large governments to run large wars), and of course many more violent injuries and deaths.

It’s also the case that once Protestant reformers arose, opportunistic rulers began to promote them, precisely so they could tear down the legitimacy of the Church and get their hands on its property.

One of the first reformers, an Englishman named John Wycliffe, began condemning the excesses of the Church during the mid-1300s, as well as translating parts of the Bible into English, which the Church had forbidden in any language but Latin. Seeing this, a powerful prince named John of Gaunt supported Wycliffe and his followers. What Gaunt and his associates wanted was both the legitimacy and the land holdings of the Church, or at least as much of them as they could get.

This pattern held throughout the Protestant reformation. This is not to say that the reformers themselves were servants of the rulers; these were brave and serious people, not accomplices. Nonetheless the rulers took advantage of them and used them for their own purposes.

The Re-Centralizing

It is a common human failing to be over-awed by things powerful and large, and to find comfort by submerging themselves within them. And so, as rulership centralized into larger and larger units, people began to be awed by them and to identify with them: to conceive of themselves less as an individual and more as a member of the the great, powerful and superior entity.

One source of legitimacy for this era’s rulers was to be an upholder of the law, the enforcer of righteousness. And so kings began in earnest to seize the mechanisms of justice, and to present themselves as its ultimate enforcer. This carried a secondary benefit of the king being able to control a huge number of human interactions in the areas they dominated. So long as crimes and abuses could be imagined occurring anywhere, the king’s sword of justice could be called upon to reach there.

Another source of legitimacy was simple geography. Once a ruler made enough theatrical proclamations on the greatness of “our land,” the inhabitants could praise themselves by championing their king.

Yet another source of legitimacy for the king was to be the bestower of honors. Once people are given “royal awards,” they and their families will have their self-image tied to the king. More than that, the majority of people hearing it will form an image of the king (or whatever royal) as above everyone else, able to confer awards from above.

As all of this was sinking roots, the middle levels of the nobility (which often involved six or more layers of interlocking land ownership) were collapsing, giving the monarch a much more direct relationship with farmers, merchants and other non-elite people.

By about 1400 AD, Europe had become a continent of relatively few and large monarchies; monarchies that grew fewer and larger over the following centuries.

At the same time, the Church lost a tremendous amount of influence, including almost all influence in Protestant countries, which by 1600 included roughly half of Europe.

Italy And The Renaissance

Italy had been different from the rest of Europe ever since Rome fell apart. Because of the land itself (much of it being mountainous), it was very difficult to rule larger territories, except in the Po Valley in the north. And so Italy had far more city-states, more independent castles, and because the church was centered there, more schools and more money transfers. It was less centralized and more commercial.

By 1293 the merchants of Florence had removed and dis-empowered the violent nobles who had previous run the city, and created a republic. This, in turn, spawned a tremendous outbreak of artistry and literature, which is called the Italian Renaissance. This “rebirth” period ran from roughly 1400 to 1600 AD, and it changed the way many Europeans thought of themselves. People began to see themselves as individuals with their own unique lives, which gave them confidence to attempt improvements they previously hadn’t imagined.

More than that, other cities tried to copy Florence, and to make themselves republics. These republican experiments didn’t usually last terribly long, but they kept inspiring new experiments. One had only to visit the city of Florence to see that experiment’s very impressive results.

Probably the greatest effect of the Renaissance was that people began imagining themselves as able to do great things. Individual genius became something that people recognized as a real possibility.

END

LESSON PLAN

As always, go slowly and be sure the students understand the lesson as completely as possible.

This lesson shows how the “First Europe” of Lesson 10 (up to 1200 AD or so) changed into something else… into the pre-modern Europe of rich, powerful kings and large wars. (This was also the time of the “witch burnings”, if that comes up.)

And, as always, don’t be hesitant to take side-paths that seem fruitful. Sometimes they will be, and perhaps sometimes they won’t, but until you try, you’ll never know. Take some risks.

One of the first points made in this lesson is also an important one: people solidifying their arrangements: seeing rules and operating structures as more essential than real things. The truth is that people find a sort of refuge in abstract entities, and particularly large and hierarchical things.

For example, during the First European period, people focused on justice rather than law. Wanting to be sure damage ceased and was paid for is vastly different from wishing to punish someone for “breaking our rules.” In fact, it comes from a very different frame of mind.

And so it was during this period that people began to think less about concrete things and more about abstract things, going from “we have to stop this guy from hurting us,” to “our law must be obeyed.”

Also important is the concept of identification with a large and powerful entity. Typically, the largest entity (state and/or church) presents themselves to people as a superior type of entity: higher than man the individual. In this, people find comfort: Once they are approved by the higher entity, they have approval from a higher source than that of their problems: they have something greater than themselves calling them good. In our times we often hear this expressed as, “People need to belong to something larger than themselves.”

Identifying with something large and impressive allows people to diffuse their personal confusion and conflicts. This is a primary appeal of large rulerships, and it’s easy to accept when you’re surrounded by others who accept it.

Again I’ve italicized new and significant words. You may want to spend time on these with your students:

Crop rotation. (An excellent side-path.)

Excommunicated.

Lay. Non-clergy church members.

Parish.

Monarchs.

Intellectuals. People who make their living creating or working with ideas rather than things.

Christendom. The Christian world, especially when seen as being superior to earthly rulers.

Entity. A non-living thing that has its own existence. Governments and churches are entities, so are corporations.

Protestant. This may seem like a good side-path, but in my experience it isn’t: it too easily falls into doctrine, self-praise or self-defense. Those are not our subjects here. I suggest that you explain Protestantism directly but briefly.

Identify.

Self-image. Likewise a good concept to explain (as a friend of mine says, “self-image is destiny”), but it’s not something to major upon.

Royal. You may also wish to include aristocracy. And it’s important to specify that these are legally protected classes.

END