One oddity of this time (and it appears to have been a necessary oddity) was gift-giving. The rich and powerful of the time gave lavish gifts to one another, and often very dramatically. This seems to have been a carry-over from Roman patronage, and, according to historian Peter Brown, it became “treasured as the cement of their social world.”

One oddity of this time (and it appears to have been a necessary oddity) was gift-giving. The rich and powerful of the time gave lavish gifts to one another, and often very dramatically. This seems to have been a carry-over from Roman patronage, and, according to historian Peter Brown, it became “treasured as the cement of their social world.”

As patronage had held Rome together, so gift-giving held things together (or at least held powerful people together) in Rome’s absence. To give such gifts displayed both one’s status and one’s relationships, both of which were necessary for legitimacy. Brown goes on to note that, “this network of interpersonal acts came, in one generation, to link the Atlantic coast to the Holy Land.”

Another necessary oddity of the time was the cult of the saints: venerating saints, relics and so on. The cult of the saints, from our standpoint, seems rather strange, and quite a few people at the time thought so too, but it filled crucial needs that apparently nothing else could.

The first need it filled was what we can call social value. People need not only to feel valuable, but to display that value. This is not ideal (self-worth is better when it comes from yourself), but people do often need the respect of others. And so, by displaying your veneration of the saints at the local shrine, or perhaps making a pilgrimage to a holy site, you could display your worth and almost certainly be praised for it.

And again, with great Rome gone, people had emotional voids they needed to fill.

Another crucial need was what Peter Brown called a new therapeutic system. That is, people needed some way to redeem themselves and return to respectable standing after making notable errors. And here’s how he described this new theraputic system:

At the shrine, thieves who confessed their deeds could make reparation for their robberies. Compared with the vengeance demanded by the outside world, the justice of the saint was all that justice should be – it was manifest, swift and remarkably mild. Those who had been healed at the shrine gained from this healing a change of social status.

Thus the saints became more than purveyors of justice, they became a path to rehabilitation. And so the odd cult of the saints became a new therapeutic system.

It’s also important to discuss hierarchy in the churches. Jesus directly opposed hierarchy, going so far to say, “So shall it not be among you.” Nonetheless, hierarchy became central to Christian churches in a fairly short period of time. The orthodox church of the time was not only hierarchical, but directly carried-over a great deal of Rome’s hierarchical structure, including things like the borders of dioceses.

This was done because the world of early Christianity was deeply affected by Roman ideas of hierarchy; it had been so long built into their assumptions and expectations that they felt an overwhelming need for it, and kept finding ways to incorporate it and justify it. (Humans can be very clever that way.)

A hierarchical church structure also made sense to the people who wanted to be new rulers, and helped them to cooperate, at least at the more centralized levels, with elite churchmen.

When looking at the development of hierarchy and rulership, however, it’s necessary to note that avoiding or minimizing taxation tended to be fairly easy at this time, and so decentralization continued.

Another reason centralization declined was the path to legitimacy we noted above: Gaining a reputation as a good Christian by giving away vast expanses of land to monasteries. Rulers saw these actions as necessary to convince people they were on their side – or perhaps were the champion of Christ – but after each such gift, the ruler had less to give, making his patronage that much less attractive. And so the rulers of the era grew progressively less powerful.

People also had wide-open options at this time. There was plenty of empty land in Europe, and many people simply moved to a good piece and started farming it. But since they were almost entirely on their own, most of them also strengthened their houses to protect themselves from raiders. That is, they build small, usually wooden, castles; fortified houses, really.

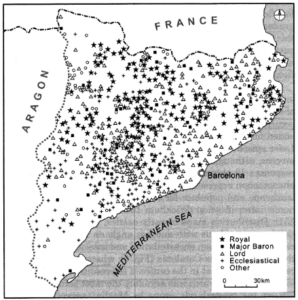

Over the first several centuries following the disappearance of Roman power, as many as 100,000 such castles were built. Italy alone had at least 26,000. Consider this map of castles in Catalonia, a province of modern Spain:

In the center of this area, castles were so thick that every three miles or so you’d run into another one. Also bear in mind that a “Lord,” as shown on this map, was probably just a person who had built and fortified his own house.

And if we assume 80,000 castles, a population of 30 million and extended families of 25 people, there was one castle for every 15 families. If you were willing to be self-responsible, you could do this. As long as you stayed away from the old cities there was probably no one to forbid you.

**

Paul Rosenberg

freemansperspective.com