Electricity And Magnetism

Electricity And Magnetism

Sparks and magnetism had long been known, but people had no understanding of what they were or how to use them in more than just a few ways, such as making magnetic compasses.

By the beginning of the 17th century people were experimenting with compasses and began making sense of the Earth’s magnetic field. A man named William Gilbert wrote that the Earth itself was a magnet in 1600 AD, and Otto von Guericke was the first person to purposely generate electricity in about the 1650s. It was also learned that the electrical force, whatever it was, could be moved from place to place with metal filaments… with wires.

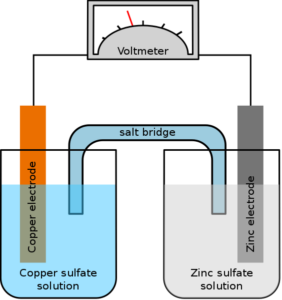

A long string of incremental discoveries followed, and by 1800 Alessandro Volta of Italy was using chemicals to generate electricity. That is, Volta was producing electrical batteries, like the one shown below.

The chemicals in a battery produce electrical charges, which create a voltage, as in this diagram. (And yes, “voltage” was named in honor of Allesandro Volta.) The movement of electrical charges is called current. And as the current flows, the chemicals change, depleting the number of electrical charges they can produce. We then say that the battery is worn out, exhausted or discharged.

Some modern batteries can be recharged by running electricity through them in the opposite direction, changing their chemicals back to their original state.

In 1820, Hans Christen Orsted of Denmark discovered that electrical currents produce magnetism. Almost immediately, Andre-Marie Ampere of France began turning Orsted’s discovery into formulas and into new experiments with new discoveries.

The next year, in 1821, Michael Faraday of England used this information to create the first electric motor. Faraday went on to discover (in 1831) that whenever a magnetic field passed through a conductor (like a wire), it automatically generated an electrical force.

Electrical motors, from Faraday onward, generally operate this way:

- You send an electrical current through a wire or coil of wires, which creates a magnetic field. (This is a universal law of electricity and magnetism: Every electrical current generates a magnetic field, and every magnetic field that passes over a conductor generates a current.)

- You arrange for a magnet to be placed near the field generated in step #1, and you attach it to a rotating shaft. The magnetic field then attracts or repels the magnet, turning the shaft.

- You arrange some way keep the process going. People learned to do this with multiple coils of wire, turned on one after another, and in many other clever ways.

You can make a simple motor with a coil of wire, a battery and a couple of paper clips.

In 1827, George Ohm of Germany discovered the laws governing electrical circuits.

By the 1840s, what had been discovered up to this point was being put to use in the form of the telegraph, sending coded messages, instantly, between any two points that could be connected with wires. In America, telegraph lines reached from coast to coast by 1861.

By 1862, James Clerk Maxwell of England produced the primary laws of electricity and magnetism that not only described precisely how it all worked, but predicted things like radio waves, which had yet to be imagined.

From there on, a long string of inventions changed the world: Telephones, electrical power, better motors, better generators and more useful types of current (alternating current), new motors, the electric light bulb (important because of its safety and low cost), and the ability to transmit electricity, affordably, over great distances. Radio followed, then much more.

Electrical power is far easier and more efficient to distribute than any other form of power we know. More than that, it can be used in tiny amounts as well as large. Immensely precise control is possible. We can even do exotic things with electricity, like reversing currents millions of times per second. All of this led directly to modern electronics, computers and other previously unimagined things.

We couldn’t have a modern world without electricity being used almost everywhere.

The Steam Engine

But while electricity was still being developed, another tremendous and practical source of power was found: the steam engine. The concepts of air pressure and vacuum (negative air pressure) had been clarified over the 17th century, and people had long realized that the power of steam could be used, but no one had been able to develop the concept.

By 1712 a man named Newcomen had developed an early steam engine. It wasn’t very efficient and couldn’t be used for terribly many things, but it did work. Then, in 1774, a man named James Watt announced that he had built, and would be pleased to sell, functional steam engines.

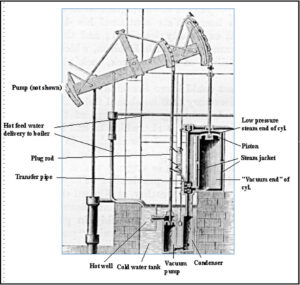

Watt’s engine, which he continually improved, was a complex machine, with a boiler to make steam, a separate condenser to cool the steam back into water, pipes, valves and a piston to create movement that could power a machine. It looked like this:

In the cutaway drawing below you can see the parts of one of Watt’s first engines.

As we noted in Lesson 12, this engine, and variations of it, powered the industrial revolution.

Before very long, new configurations of the steam engine were being used to power railroad engines. By the 1830s they were being used through Europe, North America and other places. Soon they replaced the transportation of goods via rivers and canals. Railroads spread wildly; they were simply faster, easier, and could transport goods in larger amounts. Among other things, this transformed rural areas, allowing them to get distant supplies cheaply and quickly.

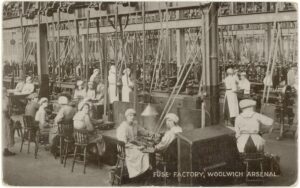

In this old photo, you can see how steam engines were used in factories. An engine (out of view in this picture) was used to turn drive shafts mounted below the ceiling of the factory, and a large number of belts brought power to each work station. (There were often middle steps as well.) This is how power was transmitted and used until electrical power replaced steam in the 20th century.

Watt’s steam engines, and more or less all steam engines, burned coal as their initial power source.

**

Paul Rosenberg

freemansperspective.com